A Symphony of Camels

The key to having a meaningful visit to the camel market at Imbaba is to get there early, before the “tourists” arrive. We woke up at 6:00 am and by 6:30 am we were standing in Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo, trying to hail a taxi. At the best of times, Tahrir (literally, Liberation) was a noisy melange of car and bus horns, people yelling, vendors hawking their wares, pollution and confusion, all contrasted by the propinquity (and historicity) of the Egyptian Museum, with its treasures of civilizations past. We had already spent several days in the City of 1000 Minarets, and it seemed as if most people spoke at least a little English. Now all of a sudden, when we needed a knowledgeable driver, not one could fathom the English language. When I asked a driver to take us to Imbaba, he just stared at me as if I was crazy. With mouth agape, he said nothing. With a vacant “just-another-tourist” look on his face, he wrinkled his brow in consternation, shrugged, and then drove off. A second driver at least pretended to understand that we wanted to go to Imbaba but he kept repeating, almost inanely, "imbaba?" "imbaba?" " want go Imbaba?" We kept saying “Yes”, and he kept up the interrogation. Finally he communicated to us that it would cost the equivalent of $3.00 Canadian. We hopped into the taxi but quickly discovered that he really had no clue where to go. After he stopped several times to ask for directions, his grasp of the English vocabulary miraculously took hold and in almost fluent tones, he turned to us and demanded $2.00 more for the trip. By this time we just wanted to get there so we agreed, and off we went. The Imbaba Camel Market turned out to be next to the Imbaba airport, a small military facility across some railway tracks, in a very isolated area, about 30 minutes outside of Cairo. We paid the $5.00, walked though a gateway into an enclosed field and apparently, we were there. At that time of day, we were the only tourists amidst hundreds of goats, donkeys and camels.

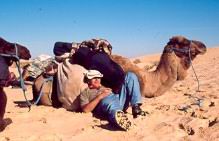

Camels everywhere. Camels in herds. Camels being shipped in on flatbed trucks from the Sudan. Camels sleeping in groups. Dusty, dirty camels. Young and old camels. Camels coughing, eating, belching and farting. Baby camels suckling and bleeting; Camels grunting, crying and protesting, all with an irritated look of surprise, disgust, annoyance, disdain and non-chalance. I had never seen so many camels in my life.

Sleepy-eyed, unshaven men were folding up their bedding that mostly consisted of faded blankets, and sometimes of straw and rags. Strong, tanned women, whose faces reflected, if not triumph, then at least a controlled mastery over a harsh lifestyle, were whisking the family areas clean. Thursday was market day in Imbaba and selling camels was the name of the game. Unwashed, gangly children who appeared to be no more that 7 or 8 years old were carrying large, flat trays of freshly baked breads and buns on their heads. Vendors were setting up their market stalls with bright cloth, tasty food treats, cold drinks and camel decorations in all shapes and forms. Bright, neon-coloured pom-poms for the bridle, richly decorated cloth for the saddle blanket and good luck charms to hang from the reins. Throughout the market area there lay wooden carts piled high with papyrus leaves to feed the goats, donkeys and camels until their sale was finalized.

One tall man stood out in the crowd. He had a straggly beard, a turban-like head-dress and a faded blue galabiah. He carried a think stick in his right hand and, for every appearance, looked as if he were conducting an orchestra. His job was to control access to the water trough. One by one the herdsmen would lead small groups of camels to the trough and the conductor would use his baton to either let the camels approach and drink, or to wait their turn, or to move on after slaking their thirst. He communicated by making camel sounds of “gwraa-gwraa”, waving the baton and often using it like a switch to beat back the more enthusiastic beasts. The slurping, inhaling, sucking, guzzling, drooling, splashing sounds of the thirsty camels combined with the clucking, yelling, grunting gwraa-gwraa of the orchestra conductor, creating a chaotic, poetic harmony. It was an amazing feat of choreography: a tumultuous, cacophonous symphony of camels.

The Imbaba locals reacted to our presence with a mixture of curiosity and friendliness. Some were from the immediate area, others had travelled from distant towns in Egypt and several had journeyed from as far south as the Sudan, making the forty-eight hour drive to sell their prize possessions at Imbaba. Harsh, strong, tall and fearsome looking men walked right by us saying "how-are-you" in a monotone staccato, but didn't wait for an answer. One man wandered over and out of the blue, offered us a Marlboro cigarette. I wondered if he was out of Camels. Indicating that we didn't smoke, we gave him a Canadian flag pin. He rushed over to show it to some other men and all of a sudden, everyone had to have a pin. With smiles and warmth, a crowd quickly surrounded my friend and I and started shouting with out-held hands, "for baby" (and making a cradling gesture); "for children", said another as he indicated the various heights of his children with a palm-down hand gesture). We were the hit of the market. We became instant celebrities, and afterward as we walked around gawking at camels, taking reams of photos and giving out even more flag pins, it seemed that we had developed an affinity with the people.

When we departed about two hours later, the regular regimen of tourist buses began to disgorge their contents, and the atmosphere quickly changed. The tension grew slightly, but this too was a necessary part of commercial life and, to many of the herdsmen and their families, survival itself. We empathized with the looks on the faces of the Imbaba gang as the first group of tourists scared a flock of goats and surrounded a terrified, wide-eyed baby camel.

The tourists had arrived.

There went the neighbourhood.

Read more at http://www.broowaha.com/articles/14844/a-symphony-of-camels#2ak3l8Rj23c4Fd2i.99

Camels everywhere. Camels in herds. Camels being shipped in on flatbed trucks from the Sudan. Camels sleeping in groups. Dusty, dirty camels. Young and old camels. Camels coughing, eating, belching and farting. Baby camels suckling and bleeting; Camels grunting, crying and protesting, all with an irritated look of surprise, disgust, annoyance, disdain and non-chalance. I had never seen so many camels in my life.

Sleepy-eyed, unshaven men were folding up their bedding that mostly consisted of faded blankets, and sometimes of straw and rags. Strong, tanned women, whose faces reflected, if not triumph, then at least a controlled mastery over a harsh lifestyle, were whisking the family areas clean. Thursday was market day in Imbaba and selling camels was the name of the game. Unwashed, gangly children who appeared to be no more that 7 or 8 years old were carrying large, flat trays of freshly baked breads and buns on their heads. Vendors were setting up their market stalls with bright cloth, tasty food treats, cold drinks and camel decorations in all shapes and forms. Bright, neon-coloured pom-poms for the bridle, richly decorated cloth for the saddle blanket and good luck charms to hang from the reins. Throughout the market area there lay wooden carts piled high with papyrus leaves to feed the goats, donkeys and camels until their sale was finalized.

One tall man stood out in the crowd. He had a straggly beard, a turban-like head-dress and a faded blue galabiah. He carried a think stick in his right hand and, for every appearance, looked as if he were conducting an orchestra. His job was to control access to the water trough. One by one the herdsmen would lead small groups of camels to the trough and the conductor would use his baton to either let the camels approach and drink, or to wait their turn, or to move on after slaking their thirst. He communicated by making camel sounds of “gwraa-gwraa”, waving the baton and often using it like a switch to beat back the more enthusiastic beasts. The slurping, inhaling, sucking, guzzling, drooling, splashing sounds of the thirsty camels combined with the clucking, yelling, grunting gwraa-gwraa of the orchestra conductor, creating a chaotic, poetic harmony. It was an amazing feat of choreography: a tumultuous, cacophonous symphony of camels.

The Imbaba locals reacted to our presence with a mixture of curiosity and friendliness. Some were from the immediate area, others had travelled from distant towns in Egypt and several had journeyed from as far south as the Sudan, making the forty-eight hour drive to sell their prize possessions at Imbaba. Harsh, strong, tall and fearsome looking men walked right by us saying "how-are-you" in a monotone staccato, but didn't wait for an answer. One man wandered over and out of the blue, offered us a Marlboro cigarette. I wondered if he was out of Camels. Indicating that we didn't smoke, we gave him a Canadian flag pin. He rushed over to show it to some other men and all of a sudden, everyone had to have a pin. With smiles and warmth, a crowd quickly surrounded my friend and I and started shouting with out-held hands, "for baby" (and making a cradling gesture); "for children", said another as he indicated the various heights of his children with a palm-down hand gesture). We were the hit of the market. We became instant celebrities, and afterward as we walked around gawking at camels, taking reams of photos and giving out even more flag pins, it seemed that we had developed an affinity with the people.

When we departed about two hours later, the regular regimen of tourist buses began to disgorge their contents, and the atmosphere quickly changed. The tension grew slightly, but this too was a necessary part of commercial life and, to many of the herdsmen and their families, survival itself. We empathized with the looks on the faces of the Imbaba gang as the first group of tourists scared a flock of goats and surrounded a terrified, wide-eyed baby camel.

The tourists had arrived.

There went the neighbourhood.

Read more at http://www.broowaha.com/articles/14844/a-symphony-of-camels#2ak3l8Rj23c4Fd2i.99