Pining for Algonquin

The mystical strain of a loon’s cry is only one of the magnetic draws of Algonquin Park, nestled on the cusp of central and northern Ontario, about three hours drive from Toronto. The sensory appeal of this escape from routines, schedules, the city and stress has been luring me to return, time and time again over the past forty years. Sometimes it’s a pilgrimage to my favourite rocky outpost on Smoke Lake to read a book, reflect and listen to the noises of silent solitude of the lake, trees and birds. Sometimes it’s a drive to the Visitor Centre, about 25 miles past the west entrance of the park, to wander through the exhibits and walk out on the platform to see a world of multi-coloured trees in the Fall; and sometimes it’s a morning-fresh hike on one of the trails with names such as Hardwood Lookout, Hemlock Bluff or Spruce Bog Boardwalk. But all the names in the park sing enchantment to me. In the past when I was the Tripper and Canoe Instructor at a summer camp we would take the kids to Lake Opeongo or Lake of Two Rivers and then in later years there was a memorable circular canoe trip with Mike Cherney, mostly in pouring rain, from Kiosk to Three Mile Lake to Manitou Lake. Algonquin has long been imprinted in my mind, as the equivalent of serenity and pleasure.

Water can do so many things in Algonquin Park. It ripples against the shiny stones, rocks and boulders on the shoreline of camp and portage sites. It slaps against the canoe, mostly to the sole accompaniment of the prevailing wind. It drips from wooden canoe paddles as we cross the lakes, in awe of the gnarled trees that died years before and left their artistic skeletons half submerged near shorelines. And the wind is no less creative when it comes to whistling and whispering through the pine trees and sending the sweet, green scent of pine needles down the hills and across the waters.

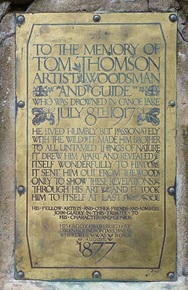

One of my first stops in the Park is the Portage Store at Canoe Lake. The fiery, musky odour of used camping equipment is ever-present and reminds me of the bitter-sweet end of canoe trips where we would have to pack up the equipment and head back to our city routines. And Canoe Lake itself has an alluring draw for Tom Thomson fans. Thomson was one of the Canadian nature painters who influenced the artists that later came to be known as the Group of Seven. His paintings, notably the Jack Pine and the West Wind, established him as a founder of nature-impressionism in Canada, and it was on Canoe Lake on July 8, 1917 that he mysteriously drowned.

To put this into another perspective; I spent some time in the Czech Republic and Austria earlier this summer discovering, amongst other things, the works of the artist Egon Schiele who lived from 1890 to 1918 and is regarded, along with Gustave Klimt, and one of the early proponents of impressionism. Just before I left Canada, I saw the documentary film on Tom Thomson’s life, entitled ‘The West Wind’, which noted Thomson’s journey toward impressionism at the same time that the movement was taking hold in Europe. I carried these thoughts with me and, upon gazing at Egon Schiele’s painting of Four Trees in the Belvedere Palace in Vienna, I saw links to the paintings that Tom Thomson was creating. To me this spoke of artistic genius, on both sides of the Atlantic, in the interpretation of nature, beyond the school of still-life, and into the realm of emotions and senses. In my mind, my two favourite artists had some kind of psychic affinity, although they lived worlds apart. But then again, such affinity amongst different peoples defines the very nature of global travel and discovery.

When I first visited Algonquin Park some forty years ago, we paddled across Canoe Lake, and then docked and secured our canoes amongst the scattered rocks at Hayhurst Point. We climbed a small hill and gathered at the base of the stone cairn, memorializing the life of Tom Thomson. And on August 2, 2012, I had the pleasure of introducing a friend, who had never canoed in his life, to the same experience of paying tribute of one of Canada’s finest artists, but also to indulge in a taste of Algonquin Park’s lakes, pine trees, wind and heritage.

We climbed up the small hill at Hayhurst Point and through a parting in the trees we could see, off in the distance, a wooden red canoe crossing Canoe Lake. And the same appreciation of this vista moved us to capture the scene with our digital cameras, just as it moved Tom Thomson to express his thoughts in oils and pastels.

The wind picked up and my friend asked about the steady, rushing noise we were hearing.I explained, that it was the wind rustling through the pine trees, a sound he had never heard before.

Shortly afterward we paddled back to Canoe Lake, this time against the wind and through small waves that forced us to paddle hard and deep. We hugged the shore to look one more time at the trees, the drift wood, the rocks and remnants of old docks, and finally after an hour, we were back at the portage store. And while now I'm in my office in Toronto surrounded by technology and noise, thoughts of Algonquin’s serenity are with me and plans to escape again are imminent.

Travel escapism is not restricted to journey’s overseas or to far flung destinations. Travel is sometimes most appreciated when it is within arm’s reach: far enough to conjure up memories of good times past as well as to appreciate the change in climate from stress to tranquility, but close enough to get away when it’s needed.

For the accompanying slide show to this blog, please visit the Be There with Me page on this website.

Water can do so many things in Algonquin Park. It ripples against the shiny stones, rocks and boulders on the shoreline of camp and portage sites. It slaps against the canoe, mostly to the sole accompaniment of the prevailing wind. It drips from wooden canoe paddles as we cross the lakes, in awe of the gnarled trees that died years before and left their artistic skeletons half submerged near shorelines. And the wind is no less creative when it comes to whistling and whispering through the pine trees and sending the sweet, green scent of pine needles down the hills and across the waters.

One of my first stops in the Park is the Portage Store at Canoe Lake. The fiery, musky odour of used camping equipment is ever-present and reminds me of the bitter-sweet end of canoe trips where we would have to pack up the equipment and head back to our city routines. And Canoe Lake itself has an alluring draw for Tom Thomson fans. Thomson was one of the Canadian nature painters who influenced the artists that later came to be known as the Group of Seven. His paintings, notably the Jack Pine and the West Wind, established him as a founder of nature-impressionism in Canada, and it was on Canoe Lake on July 8, 1917 that he mysteriously drowned.

To put this into another perspective; I spent some time in the Czech Republic and Austria earlier this summer discovering, amongst other things, the works of the artist Egon Schiele who lived from 1890 to 1918 and is regarded, along with Gustave Klimt, and one of the early proponents of impressionism. Just before I left Canada, I saw the documentary film on Tom Thomson’s life, entitled ‘The West Wind’, which noted Thomson’s journey toward impressionism at the same time that the movement was taking hold in Europe. I carried these thoughts with me and, upon gazing at Egon Schiele’s painting of Four Trees in the Belvedere Palace in Vienna, I saw links to the paintings that Tom Thomson was creating. To me this spoke of artistic genius, on both sides of the Atlantic, in the interpretation of nature, beyond the school of still-life, and into the realm of emotions and senses. In my mind, my two favourite artists had some kind of psychic affinity, although they lived worlds apart. But then again, such affinity amongst different peoples defines the very nature of global travel and discovery.

When I first visited Algonquin Park some forty years ago, we paddled across Canoe Lake, and then docked and secured our canoes amongst the scattered rocks at Hayhurst Point. We climbed a small hill and gathered at the base of the stone cairn, memorializing the life of Tom Thomson. And on August 2, 2012, I had the pleasure of introducing a friend, who had never canoed in his life, to the same experience of paying tribute of one of Canada’s finest artists, but also to indulge in a taste of Algonquin Park’s lakes, pine trees, wind and heritage.

We climbed up the small hill at Hayhurst Point and through a parting in the trees we could see, off in the distance, a wooden red canoe crossing Canoe Lake. And the same appreciation of this vista moved us to capture the scene with our digital cameras, just as it moved Tom Thomson to express his thoughts in oils and pastels.

The wind picked up and my friend asked about the steady, rushing noise we were hearing.I explained, that it was the wind rustling through the pine trees, a sound he had never heard before.

Shortly afterward we paddled back to Canoe Lake, this time against the wind and through small waves that forced us to paddle hard and deep. We hugged the shore to look one more time at the trees, the drift wood, the rocks and remnants of old docks, and finally after an hour, we were back at the portage store. And while now I'm in my office in Toronto surrounded by technology and noise, thoughts of Algonquin’s serenity are with me and plans to escape again are imminent.

Travel escapism is not restricted to journey’s overseas or to far flung destinations. Travel is sometimes most appreciated when it is within arm’s reach: far enough to conjure up memories of good times past as well as to appreciate the change in climate from stress to tranquility, but close enough to get away when it’s needed.

For the accompanying slide show to this blog, please visit the Be There with Me page on this website.